|

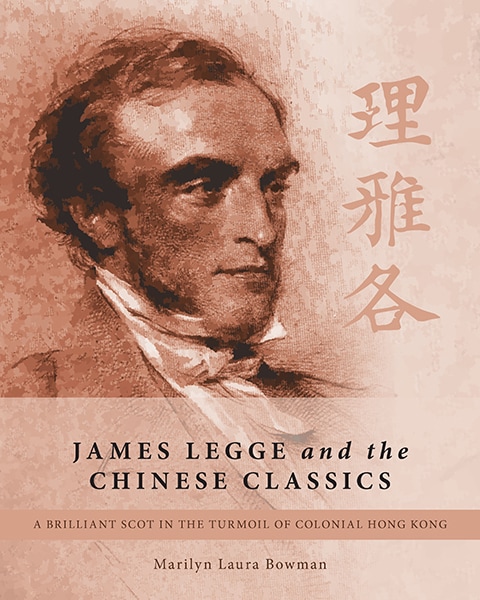

JAMES LEGGE AND THE CHINESE CLASSICS

A Brilliant Scot in the Turmoil of Colonial Hong Kong FriesenPress (August 31, 2016) James Legge (1815-1897), was a great Scots scholar and missionary famed as a translator of the Chinese Classics when struggles between Britain and China included two wars. It was an era of sailing ships, pirates, opium wars, the swashbuckling East India Company, cannibals eating missionaries, and the opening of Qing China to trade and ideas. Legge was vilified by fundamentalist missionaries who disagreed with his favourable views about Chinese culture and beliefs. He risked beheading twice while helping Chinese individuals being terrorized during the Taiping Rebellion. He became so ill from Hong Kong fevers when only 29 that he was forced to return to the UK to save his life. Recovering, he and his three talented Chinese students attracted such interest that they were invited to a private meeting with Queen Victoria. Legge thrived despite serious illnesses, lost five of his 11 children and both wives to premature deaths, survived cholera epidemics, typhoons, and massive fires. He was poisoned twice in a famous scandal, helped save a sailing ship from fire on the high seas, took in a bohemian Qing scholar on the run, foiled a bank-bombing plot, and earned enmity in the colony for providing court testimony about translation that favoured accused Chinese men rather than the colonial authorities. Legge’s resilient responses and incredible productivity reflected the passion he had developed at the age of 23 for understanding the culture of China. He retired to become a Fellow of Corpus Christi College and the first Professor of Chinese. |

Reviews

No Longer Forgotten: The Resuscitation of the Pioneering Missionary, Sinologist, Comparative Religionist, and

Educational Innovator James Legge (1815-1897)

Norman Girardot

University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Lehigh University, USA

[email protected]

A Review of: Marilyn Laura Bowman’s James Legge and the Chinese Classics A Brilliant Scot in the Turmoil of Colonial Hong Kong. Fort St. Victoria Canada: Friesen Press, 2016. 614 pages.

For almost one hundred years James Legge – the great 19th century Scottish missionary, translator of the Chinese Classics, active participant in the shaping of Hong Kong, and first professor of Chinese at Oxford University – had been mostly forgotten in the annals of formative pioneers in the intellectual and cultural history of the Western intercourse with, and understanding of, Chinese tradition. There were many reasons for this neglect not the least of which was the prevailing (and often justified) 20th century secularist bias of a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” or “Orientalism” as it came to be called, regarding the motives of the British imperial agenda which was seen to distort the motives of the Protestant missionary movement.

In this sense, even Legge’s truly groundbreaking achievements as a translator and scholar of the Chinese Classics and the comparative study of Chinese religion were frequently trivialized, criticized as hopelessly one-sided, or simply ignored as an outdated example of a stilted and prejudiced Victorian scholarship. Indeed Marilyn Bowman ends her examination of Legge’s life and work with an Epilogue that interestingly reviews, and in many ways puts to rest, this unfortunate history of neglect. However Bowman’s book does not singlehandedly accomplish this resuscitation of Legge’s greatness and ongoing significance. In fact in the past twenty years there has been a boomlet of interest in Legge’s contributions to missionary history, Scottish intellectual tradition, the comparative history of religions, translation theory, British relations with China, and the overall checkered history of cross-cultural understanding. These developments are seen in a series of very substantial books (e.g., my own book in 2002 and the books by Lauren Pfister, 2004, and M. K. Wong in 2000) as well as numerous articles and conferences.

With this much recent attention about Legge and his legacy, one may wonder what Bowman’s massive book (614 double-columned pages!) can add to our understanding. In this regard I am happy to report that Bowman, as an academic clinical psychologist with a special interest the human response to existential challenges and Asia, gives us a vastly expanded, meticulously researched, and insightful portrait of Legge’s personal and intellectual development – particularly with regard to his Scottish religious and intellectual heritage and his intimate involvement with colonial Hong Kong’s missionary, educational, cultural, and political history. Pfister and Wong also deal with many aspects of Legge’s missionary activities in Hong Kong, but no one has presented so fully and effectively the broad human and cultural dynamic of Legge’s career in 19th century Hong Kong. My own work focused on Legge’s relationship with Max Müller and the emergence of an academic and “comparative” approach to the study of the so-called “Sacred Books of the East” and the “world religions.”

It is a fascinating and at times quite poignant story that Bowman has to tell and despite what at first glance appears to be an egregious violation of Lytton Strachey’s dictum that biographers should always sacrifice overly abundant detail in the interest of strategic selection and amusing anecdotal dramatization (see his Eminent Victorians, 1918; and I must admit that I am also a sinner in this regard), Bowman writes with a fluid accessibility, a talent for highlighting the entanglement of emotional and intellectual issues, and a merciful avoidance of academic jargon. Yes, this is a very long book, but it has a momentum and engaging appeal enlivened by telling many evocative tales – whether instructive, comical, or simply sad – associated with colonial life, scholarly bickering, and missionary intrigue. Bowman has written a surprisingly sprightly narrative.

With regard Hong Kong colonial history, I will only draw attention here to a few broad issues. It is worth noting that in addition to his identity and prominence at a missionary and scholar, Legge’s contributions to Hong Kong social, political, and religious life were amazingly multifaceted. This includes, for example and without trying to assign any special ranking, such accomplishments as his overall civic engagement and progressive social and cultural agenda; his reformation of missionary and public education; his role in the introduction of Western methods of mechanical printing and the use of movable metal type; his liberal attitude toward the establishment of an indigenous Chinese Christian church tradition that did not depend on the gross number of not-very-sincere “converts”; and his atypical public recognition of, and sincere respect, for his Chinese religious and scholarly assistants. Also instructive are the descriptions of Legge’s life as a family man and the colonial social dynamics in the face of multiple calamities of fever, death, crime, fire, and poisoning; obstruction from the London Missionary Society (LMS); and nationalistic squabbling between British and Americans.

In many ways, Bowman’s account in the many sections devoted to Malacca, Hong Kong, and the various trips back and forth to Scotland and England (chapters 16 through 49) gives us informative miniature histories of many different but interrelated and frequently controversial topics, issues, and people. Notable among these are matters relating to the history of, and struggle between, Britain and China and the evolving nature of missionary policy and scholarship such as the rancorous battles over a Chinese version of the Bible as related to the hotly contested “term question” about the translation of “God.” Also noteworthy are her deft discussions of prominent Chinese such as the reforming scholar Wang Tao and pastor Ho Tsunshin; the complications of the Taiping rebellion and its syncretistic absorption of Christianity; and the eccentricities and duplicitous actions of various prominent missionaries (perhaps most notoriously, Charles Gutzlaff). To say the least, this is frequently quite colorful as well as periodically and sometimes simultaneously both optimistic and disturbing.

Amidst all of the riches of discerning historical description in the many pages devoted to Hong Kong, Bowman’s concluding sections about “Life, Beliefs, and Attitudes” (Parts 13 and 14) are also replete with many shrewd psychological reflections on Legge’s resilient character. Most of all, Legge was someone – throughout his life in Scotland, Hong Kong, and England – who displayed a great “psychological robustness” in the face of extreme personal and professional challenges. Bowman’s analysis does not add much to theories about how and to what degree or combination “nature and nurture” contributed to a Legge’s psychological make-up. But more helpfully if somewhat obviously after so much revealing personal detail, she concludes that Legge was fundamentally a “sanguine” person of very rare linguistic and scholarly abilities who was basically “genial, kind, helpful, and self-deprecating.” He could, however, be extremely “assertive” in contentious matters of missionary policy, civic mindedness, and scholarly debate. I will only say that, in keeping with my own assessment of Legge the man and scholar, Bowman’s analysis largely rings true. There was always an intellectual assuredness on Legge’s part but never any real arrogance or religious righteousness.

In conclusion it is worth noting the 21st century irony of Legge’s specific accomplishments with respect to his role as a missionary to China and his career in Hong Kong. Legge more than most missionaries of his era had strong misgivings about the cultural rigidity of Evangelical Protestant missionary policy and the failure to recognize the antiquity and greatness of the Chinese “classical” and “sacred” tradition. In this regard he also recognized the obvious fact that in the 19th century Christianity had made little headway in terms of becoming an influential part of Chinese religious history. He always felt, however, that the careful laying a culturally sensitive groundwork of understanding and respect would in due course lead to an authentic Chinese Christianity. Legge would have wished this transformation to happen sooner rather than later, but he also knew that the foreign religious tradition of Buddhism took several centuries to be assimilated as one of the “traditional” religions of China. What is so interesting is that it is only now in the 21st century that Legge’s hope for a Chinese Christianity is actually becoming a significant reality in the still officially atheistic Peoples Republic of China (see Ian Johnson’s The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, 2017).

See the published review in the Ormsby Review, at

http://bcbooklook.com/2017/06/02/the-resuscitation-of-james-legge/

No Longer Forgotten: The Resuscitation of the Pioneering Missionary, Sinologist, Comparative Religionist, and

Educational Innovator James Legge (1815-1897)

Norman Girardot

University Distinguished Professor Emeritus, Lehigh University, USA

[email protected]

A Review of: Marilyn Laura Bowman’s James Legge and the Chinese Classics A Brilliant Scot in the Turmoil of Colonial Hong Kong. Fort St. Victoria Canada: Friesen Press, 2016. 614 pages.

For almost one hundred years James Legge – the great 19th century Scottish missionary, translator of the Chinese Classics, active participant in the shaping of Hong Kong, and first professor of Chinese at Oxford University – had been mostly forgotten in the annals of formative pioneers in the intellectual and cultural history of the Western intercourse with, and understanding of, Chinese tradition. There were many reasons for this neglect not the least of which was the prevailing (and often justified) 20th century secularist bias of a “hermeneutics of suspicion,” or “Orientalism” as it came to be called, regarding the motives of the British imperial agenda which was seen to distort the motives of the Protestant missionary movement.

In this sense, even Legge’s truly groundbreaking achievements as a translator and scholar of the Chinese Classics and the comparative study of Chinese religion were frequently trivialized, criticized as hopelessly one-sided, or simply ignored as an outdated example of a stilted and prejudiced Victorian scholarship. Indeed Marilyn Bowman ends her examination of Legge’s life and work with an Epilogue that interestingly reviews, and in many ways puts to rest, this unfortunate history of neglect. However Bowman’s book does not singlehandedly accomplish this resuscitation of Legge’s greatness and ongoing significance. In fact in the past twenty years there has been a boomlet of interest in Legge’s contributions to missionary history, Scottish intellectual tradition, the comparative history of religions, translation theory, British relations with China, and the overall checkered history of cross-cultural understanding. These developments are seen in a series of very substantial books (e.g., my own book in 2002 and the books by Lauren Pfister, 2004, and M. K. Wong in 2000) as well as numerous articles and conferences.

With this much recent attention about Legge and his legacy, one may wonder what Bowman’s massive book (614 double-columned pages!) can add to our understanding. In this regard I am happy to report that Bowman, as an academic clinical psychologist with a special interest the human response to existential challenges and Asia, gives us a vastly expanded, meticulously researched, and insightful portrait of Legge’s personal and intellectual development – particularly with regard to his Scottish religious and intellectual heritage and his intimate involvement with colonial Hong Kong’s missionary, educational, cultural, and political history. Pfister and Wong also deal with many aspects of Legge’s missionary activities in Hong Kong, but no one has presented so fully and effectively the broad human and cultural dynamic of Legge’s career in 19th century Hong Kong. My own work focused on Legge’s relationship with Max Müller and the emergence of an academic and “comparative” approach to the study of the so-called “Sacred Books of the East” and the “world religions.”

It is a fascinating and at times quite poignant story that Bowman has to tell and despite what at first glance appears to be an egregious violation of Lytton Strachey’s dictum that biographers should always sacrifice overly abundant detail in the interest of strategic selection and amusing anecdotal dramatization (see his Eminent Victorians, 1918; and I must admit that I am also a sinner in this regard), Bowman writes with a fluid accessibility, a talent for highlighting the entanglement of emotional and intellectual issues, and a merciful avoidance of academic jargon. Yes, this is a very long book, but it has a momentum and engaging appeal enlivened by telling many evocative tales – whether instructive, comical, or simply sad – associated with colonial life, scholarly bickering, and missionary intrigue. Bowman has written a surprisingly sprightly narrative.

With regard Hong Kong colonial history, I will only draw attention here to a few broad issues. It is worth noting that in addition to his identity and prominence at a missionary and scholar, Legge’s contributions to Hong Kong social, political, and religious life were amazingly multifaceted. This includes, for example and without trying to assign any special ranking, such accomplishments as his overall civic engagement and progressive social and cultural agenda; his reformation of missionary and public education; his role in the introduction of Western methods of mechanical printing and the use of movable metal type; his liberal attitude toward the establishment of an indigenous Chinese Christian church tradition that did not depend on the gross number of not-very-sincere “converts”; and his atypical public recognition of, and sincere respect, for his Chinese religious and scholarly assistants. Also instructive are the descriptions of Legge’s life as a family man and the colonial social dynamics in the face of multiple calamities of fever, death, crime, fire, and poisoning; obstruction from the London Missionary Society (LMS); and nationalistic squabbling between British and Americans.

In many ways, Bowman’s account in the many sections devoted to Malacca, Hong Kong, and the various trips back and forth to Scotland and England (chapters 16 through 49) gives us informative miniature histories of many different but interrelated and frequently controversial topics, issues, and people. Notable among these are matters relating to the history of, and struggle between, Britain and China and the evolving nature of missionary policy and scholarship such as the rancorous battles over a Chinese version of the Bible as related to the hotly contested “term question” about the translation of “God.” Also noteworthy are her deft discussions of prominent Chinese such as the reforming scholar Wang Tao and pastor Ho Tsunshin; the complications of the Taiping rebellion and its syncretistic absorption of Christianity; and the eccentricities and duplicitous actions of various prominent missionaries (perhaps most notoriously, Charles Gutzlaff). To say the least, this is frequently quite colorful as well as periodically and sometimes simultaneously both optimistic and disturbing.

Amidst all of the riches of discerning historical description in the many pages devoted to Hong Kong, Bowman’s concluding sections about “Life, Beliefs, and Attitudes” (Parts 13 and 14) are also replete with many shrewd psychological reflections on Legge’s resilient character. Most of all, Legge was someone – throughout his life in Scotland, Hong Kong, and England – who displayed a great “psychological robustness” in the face of extreme personal and professional challenges. Bowman’s analysis does not add much to theories about how and to what degree or combination “nature and nurture” contributed to a Legge’s psychological make-up. But more helpfully if somewhat obviously after so much revealing personal detail, she concludes that Legge was fundamentally a “sanguine” person of very rare linguistic and scholarly abilities who was basically “genial, kind, helpful, and self-deprecating.” He could, however, be extremely “assertive” in contentious matters of missionary policy, civic mindedness, and scholarly debate. I will only say that, in keeping with my own assessment of Legge the man and scholar, Bowman’s analysis largely rings true. There was always an intellectual assuredness on Legge’s part but never any real arrogance or religious righteousness.

In conclusion it is worth noting the 21st century irony of Legge’s specific accomplishments with respect to his role as a missionary to China and his career in Hong Kong. Legge more than most missionaries of his era had strong misgivings about the cultural rigidity of Evangelical Protestant missionary policy and the failure to recognize the antiquity and greatness of the Chinese “classical” and “sacred” tradition. In this regard he also recognized the obvious fact that in the 19th century Christianity had made little headway in terms of becoming an influential part of Chinese religious history. He always felt, however, that the careful laying a culturally sensitive groundwork of understanding and respect would in due course lead to an authentic Chinese Christianity. Legge would have wished this transformation to happen sooner rather than later, but he also knew that the foreign religious tradition of Buddhism took several centuries to be assimilated as one of the “traditional” religions of China. What is so interesting is that it is only now in the 21st century that Legge’s hope for a Chinese Christianity is actually becoming a significant reality in the still officially atheistic Peoples Republic of China (see Ian Johnson’s The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao, 2017).

See the published review in the Ormsby Review, at

http://bcbooklook.com/2017/06/02/the-resuscitation-of-james-legge/

A recent book awards competition nominated my book to the final short-list, the reviewer writing:

“To say that this book is about James Legge and the Chinese classics is, in many ways, to do it a disservice. This is a sprawling, epic story that also explores the early years of Sino-Western relations, cultural consequences of the industrial Revolution, timeless questions of theology and much more. Written in an articulate and accessible style, the book also includes stories of politics, crime, intrigue and scandal in the Victorian era. This book is a feat of significant scholarship. Meticulously research and annotated, it deserves to be on the shelves of every research library. The author makes a compelling case for renewed interest in the life and work of James Legge. In order to achieve her objective, I would like to see this book used as a source material for more compact discussions of individual topics. The list of possibilities here is impressive... I hope the author will continue her commitment to James Legge. Even if she does not, however, she has made an extremely worthwhile contribution to future scholars.” (Judge,Whistler Independent Book Awards, 2017)

“To say that this book is about James Legge and the Chinese classics is, in many ways, to do it a disservice. This is a sprawling, epic story that also explores the early years of Sino-Western relations, cultural consequences of the industrial Revolution, timeless questions of theology and much more. Written in an articulate and accessible style, the book also includes stories of politics, crime, intrigue and scandal in the Victorian era. This book is a feat of significant scholarship. Meticulously research and annotated, it deserves to be on the shelves of every research library. The author makes a compelling case for renewed interest in the life and work of James Legge. In order to achieve her objective, I would like to see this book used as a source material for more compact discussions of individual topics. The list of possibilities here is impressive... I hope the author will continue her commitment to James Legge. Even if she does not, however, she has made an extremely worthwhile contribution to future scholars.” (Judge,Whistler Independent Book Awards, 2017)

You can purchase your copy at most major online book retailers, including these...

The ebook is available on these retailers...

|

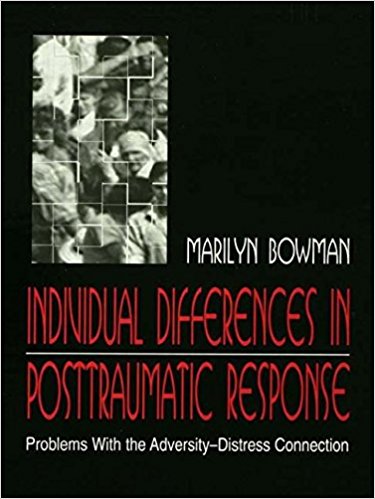

INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES IN POSTTRAUMATIC RESPONSE Problems With the Adversity-distress Connection This book challenges the assumptions of the event-dominated DSM model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Bowmam examines a series of questions directed at the current mental health model, reviewing the empirical literature. She finds that the dose-response assumptions are not supported; the severity of events is not reliably associated with PTSD, but is more reliably associated with important pre-event risk factors. She reviews evidence showing the greater role of individual differences including trait negative affectivity, belief systems, and other risk factors, in comparison with event characteristics, in predicting the disorder. The implications for treatment are significant, as treatment protocols reflect the DSM assertion that event exposure is the cause of the disorder, implying it should be the focus of treatment. Bowman also suggests that an event focus in diagnosis anad treatment risks increases the disorder because it does not provide sufficient attention to important pre-exisiting risk factors. Review of: Individual Differences in Posttraumatic Response: Problems With the Adversity-Distress Connection By: Marilyn Bowman, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1997. 189 pp. ISBN 0-8058-2713-7. $39.95 Review By: Daniel L. Creson, published in: Contemporary Psychology: APA Review of Books, Vol 43(7), Jul, 1998. pp. 499. Biographical Information for Author: Marilyn Bowman, professor emerita of psychology at Simon Fraser University (Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada), served as founding director of that department's doctoral program in clinical psychology (1977–1981) and as department chair (1977–1982). Bowman is recipient of the 1972 American Psychological Association Division 28 (Psychopharmacology and Substance Abuse) Best Dissertation Award and of the 1985 Park O. Davidson Award for distinguished contributions to psychology as it is practiced in British Columbia and is a fellow of the Canadian Psychological Association. Bowman is author of “Brain Impairment in Impulsive Violence” in C. Webster and M. Jackson (Eds.) Impulsivity: Perspectives, Principles, and Practise and “Difficulties in Assessing Personality and Predicting Behavior” in B. Beyerstein and D. Beyerstein (Eds.) The Write Stuff. Reviewer: Daniel L. Creson, professor and director of continuing education in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Texas—Houston Health Science Center, works as a major consultant to Catholic Relief Services on the Sarajevo Psychosocial Trauma Project (Phases I, II, and III) and serves as a consultant to several other organizations, including the Society for Psychological Assistance in Zagreb, Croatia, and the Humanitarian Aid and Medical Development Society in London, England. Creson is the author of several articles regarding trauma and the impact of war and natural disasters. This slender volume is a valuable addition to a growing professional debate over the nature of the relationship between traumatic life events and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—Fourth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) designators such as posttraumatic stress disorder. It raises important and inadequately understood issues such as whether the “dosage” of trauma experienced by an individual determines the seriousness of a posttraumatic disorder, and to what degree individual and group variables determine postevent pathology. Bowman avoids acrimony and an absolutist position in favor of a systematic survey of an often fragmentary and contradictory literature. What she finds in the literature she brings to bear on a series of specific and highly relevant questions that become the titles of her chapters. Most, if not all, of the author's questions have been addressed before, but rarely with the clarity and brevity that Bowman brings to this publication. Building on her opening question of whether there is a problem in understanding postevent distress, the author guides the reader through a comprehensive review of the literature as it relates to 12 additional questions, each following logically on its predecessors. The inevitable and final question is, of course, “Can professional treatments remedy event-attributed distress?” Where the author finds insufficient data for a reasonable conclusion, and this is often the case, she explores alternatives with an emphasis on the need for a more balanced view that takes into consideration the interaction of individual variables with diverse traumatic experiences. This book is, to a large degree, a critique of the assumption that traumatic events create psychopathology amenable to traditional intervention strategies. Bowman provides the reader with an interesting discussion of social context, including an unnecessary diversion through the consequences of postmodern theory, and she explores the potential contribution of various treatment approaches to the development of posttraumatic symptomatology. In this regard, Bowman warns the reader that “professionals need to understand the way the adversity-distress model might create biased belief systems in patients that will contribute to an increased incidence of emotional problems” (p. 138). Bowman's Individual Differences in Posttraumatic Response is a useful guide to the literature for those genuinely interested in the field and an important contribution in the effort to find a firm theoretical footing for future clinical work. It is not an appropriate read for someone with a casual interest or a biased perspective to defend. It is, rather, a scholar's guide to many of the essential questions that must be addressed if we are to ultimately understand the relationship between traumatic life experiences, individual genetic and developmental variables, and the impact of that relationship on subsequent behavior. Reference American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. |